Life at the Edge: The Man Who Chose Solitude on Cape Cod's Shore

Share

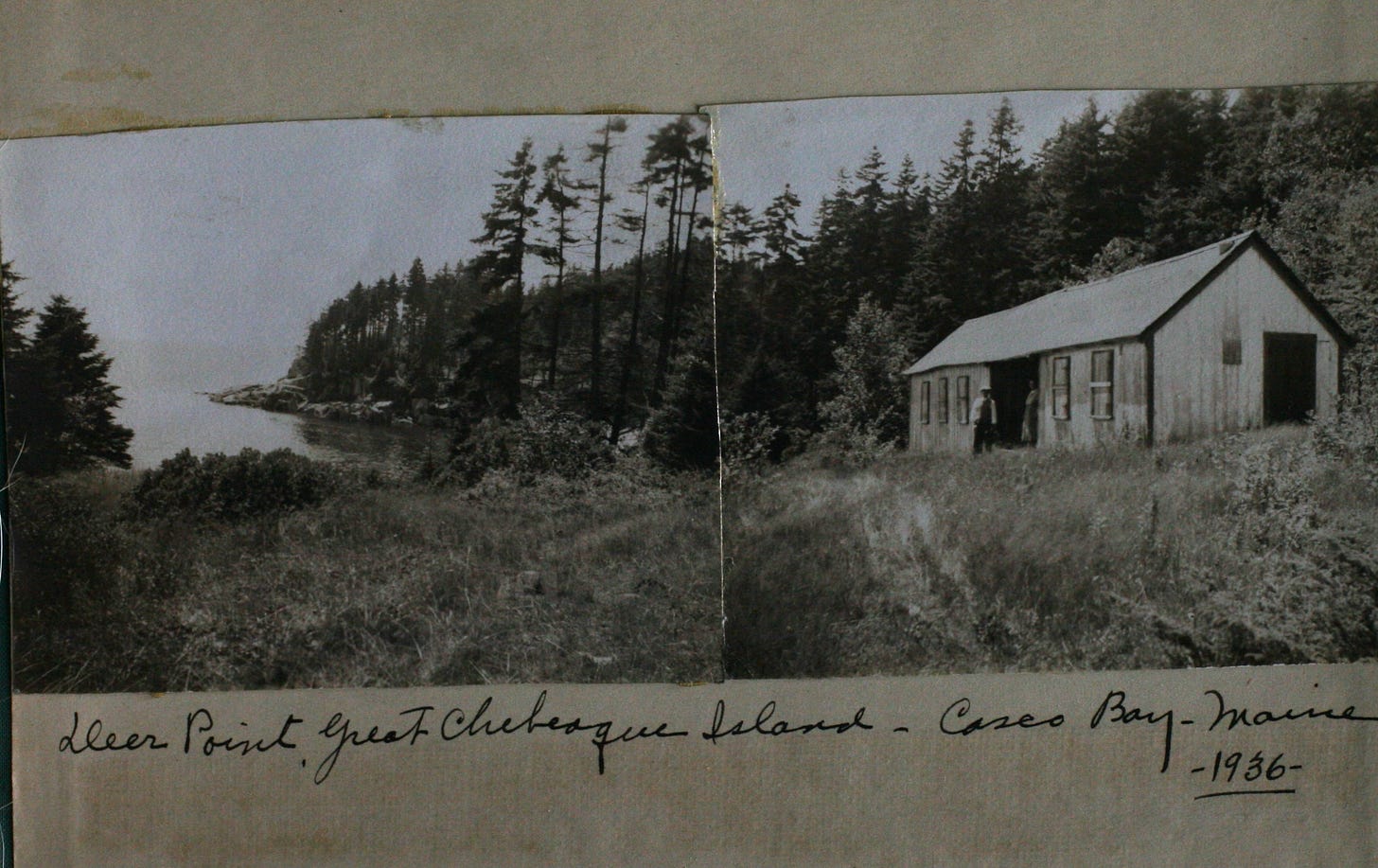

If you know me, you know I am kind of obsessed with naturalist writers and the lives they lead and the words they wrote. I found Beston's book The Outermost House, mentioned in an old yellowing article tucked into a book in an Airbnb in New Harbor, Maine one summer. It said how the sea had finally taken the house. I was struck and immediately obsessed with all things Beston. I found everything I could on him. His story captivated me. I could entirely relate to his need for a year of solitude and sea.

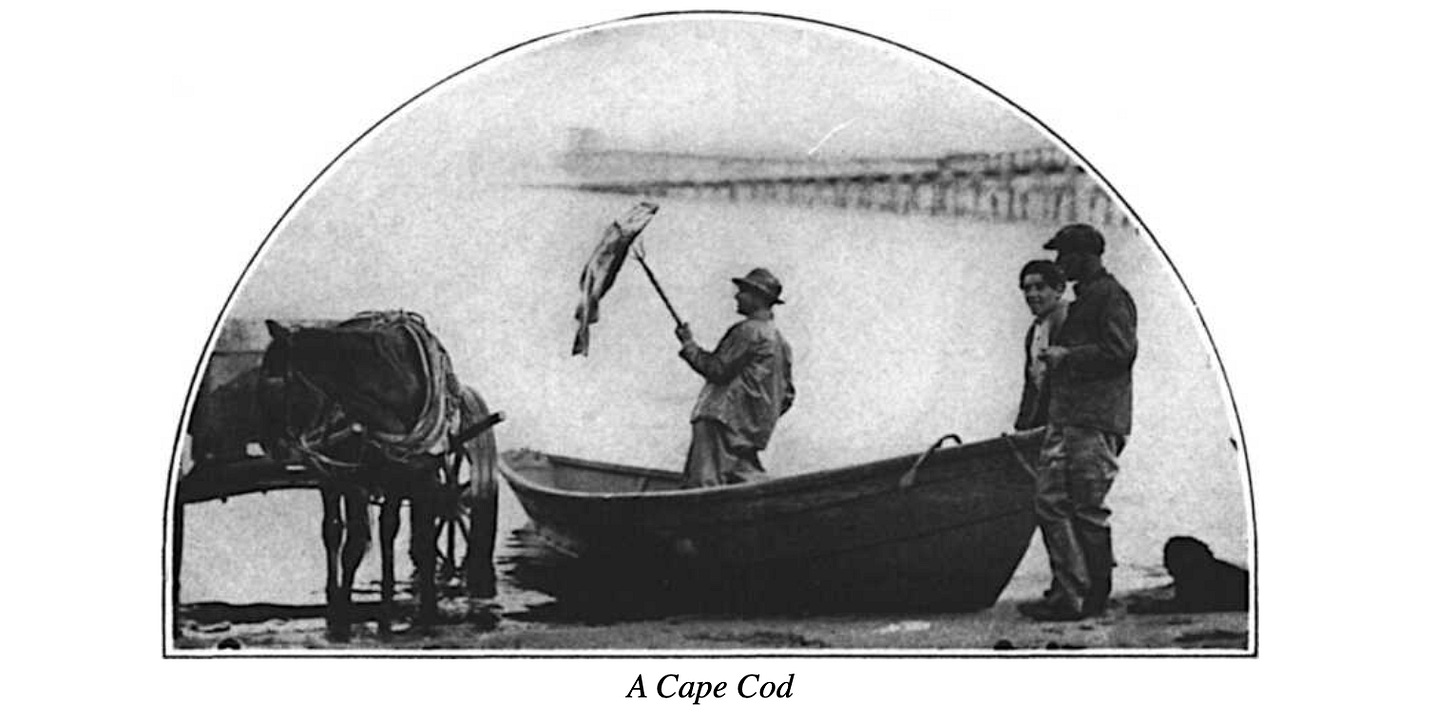

The Fo'castle, as author Henry Beston called his little house, sat on the dunes about 1.5 miles south of Coast Guard Beach in Eastham. In September 1926, Beston came intending to spend two weeks on the beach. He stayed a year, living in solitude and immersing himself in the natural world. His year by the sea provided healing from the horrors he experienced as an ambulance driver during World War I.

Henry Beston wasn't running from society – he was running toward something far more profound.

"Outermost cliff and solitary dune...this is Eastham; this is the Outer Cape...Having known and loved this land for many years, it came about that I found myself free to visit there, and so I built myself a house upon the beach." - Henry Beston

The 20x16 foot cottage was perched precariously on a dune overlooking the Atlantic Ocean near Eastham, Massachusetts. Here, with no electricity and only basic amenities, he found himself immersed in what he called the "elemental things" – the rhythms of tides, the migrations of birds, and the eternal dance of stars across the night sky.

EXCERPT

And what of Nature itself, you say—that callous and cruel engine, red in tooth and fang? Well, it is not so much of an engine as you think. As for “red in tooth and fang,” whenever I hear the phrase or its intellectual echoes I know that some passer-by has been getting life from books. It is true that there are grim arrangements. Beware of judging them by whatever human values are in style. As well expect Nature to answer to your human values as to come into your house and sit in a chair. The economy of nature, its checks and balances, its measurements of competing life—all this is its great marvel and has an ethic of its own. Live in Nature, and you will soon see that for all its non-human rhythm, it is no cave of pain. As I write I think of my beloved birds of the great beach, and of their beauty and their zest of living. And if there are fears, know also that Nature has its unexpected and unappreciated mercies.

Whatever attitude to human existence you fashion for yourself, know that it is valid only if it be the shadow of an attitude to Nature. A human life, so often likened to a spectacle upon a stage, is more justly a ritual. The ancient values of dignity, beauty, and poetry which sustain it are of Nature’s inspiration; they are born of the mystery and beauty of the world. Do no dishonour to the earth lest you dishonour the spirit of man. Hold your hands out over the earth as over a flame. To all who love her, who open to her the doors of their veins, she gives of her strength, sustaining them with her own measureless tremor of dark life. Touch the earth, love the earth, honour the earth, her plains, her valleys, her hills, and her seas; rest your spirit in her solitary places. For the gifts of life are the earth’s and they are given to all, and they are the songs of birds at daybreak, Orion and the Bear, and dawn seen over ocean from the beach.

Why did he stay so long?

The answer lies in what Beston discovered during his solitary year: a deep connection to natural cycles that modern life had severed. He wrote not as a scientist but as a poet-naturalist, describing the coast's wild beauty with an almost mystical reverence. His extended stay wasn't an escape but an awakening to what he believed humanity was increasingly forgetting – our fundamental relationship with the natural world.

"The world today is sick to its thin blood for the lack of elemental things," he wrote, "for fire before the hands, for water welling from the earth, for air, for the dear earth itself underfoot."

Tragically, the Fo'castle didn't survive forever. In 1978, after decades of serving as a National Literary Landmark, it was claimed by a fierce winter storm. Yet Beston's legacy endures, reminding us that sometimes, to truly understand our place in the world, we must first step outside of it. I loved this passage which talks about how the wind blows and connects Maine to Central America. We are all so entirely connected.

It is a singular experience to walk this brim of ocean when the wind is blowing almost directly down the beach, but now veering a point toward the dunes, now a point toward the sea. For twenty feet a humid and tropical exhalation of hot, wet sand encircles one, and from this one steps, as through a door, into as many yards of mid-September. In a point of time, one goes from Central America to Maine. - Beston

Free ebook link: https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/73328/pg73328-images.html

In an age of constant connectivity and digital noise, Beston's year of solitude and observation feels more relevant than ever. His story isn't just about a man living alone in a house on the beach – it's about rediscovering what it means to be fully human in a world that grows increasingly detached from its natural roots. And making it a priority to reconnect with your natural surroundings at all costs.